In an era of shifting alliances and economic turbulence, trade tariffs have returned as key instruments in global strategy. When the United States raises tariffs—on China, the EU, or specific sectors—the repercussions are felt far beyond American borders. These measures reshape supply chains, alter costs and redirect goods worldwide with consequences that ripple through several markets simultaneously. The UK, with its deeply globalised economy, often feels these effects even when not directly involved. Its exposure makes trade policy abroad a domestic concern with implications that extend to local jobs and prices.

For UK policymakers and businesses, the consequences of US trade tariffs are immediate and often difficult to anticipate fully. These measures affect exports, production costs and the price of essential goods across various industries in complex ways. The country cannot afford to overlook how decisions made elsewhere influence its own economy and internal market dynamics. This article examines how policies introduced in Washington reshape the UK’s trade position, revealing the often overlooked ways that tariffs abroad alter realities at home, across multiple sectors and scales.

Understanding the role of trade tariffs in global economics

Trade tariffs are import taxes. Governments use them to protect local industries or strengthen their position in negotiations globally. While they seem targeted, their effects are widespread—especially when issued by a major economy like the United States. For open markets like the UK, the spillovers can be considerable and require constant monitoring by trade analysts and policymakers.

Restricting exports in one country often means shortages or oversupply in another market, disrupting expectations. When the US limits imports from Asia or Europe, goods shift direction, prices move and markets react. British industries, even those with no direct ties to the US, end up adjusting to new conditions, facing costs or competition they hadn’t anticipated or budgeted for in their original strategies.

Pressure on UK exporters and international competitiveness

When US tariffs block goods from key exporters, the UK can become a backup destination for surplus products. These diverted goods saturate British markets, forcing local producers to compete on tighter margins in already pressured environments. In sectors like steel, ceramics or chemicals, this added pressure can cut into profits and stifle growth across the board.

Exporters also lose ground when global supply chains reconfigure due to unexpected shifts. If a supplier reroutes exports from the US to Europe, British companies may lose their place or face delays. Pricing becomes unpredictable, partnerships strain, and smaller firms struggle to respond. These changes weaken the UK’s trade resilience and leave businesses exposed to conditions beyond their control.

Disruption across British supply chains

UK manufacturers depend on inputs from multiple regions with increasingly fragile logistics. When US tariffs affect countries that supply parts or materials, British firms bear the consequences in cost and planning. Costs go up, shipments slow, and operations get squeezed, often without time to adapt properly or secure new sourcing contracts.

A tech firm in London might rely on microchips from Taiwan and assembly tools from Germany or Korea. If one of these is caught in a trade dispute, the whole chain falters, delaying production timelines. Larger companies may absorb delays, but smaller ones can’t. They face rising bills and missed deadlines, with long-term effects on competitiveness and operational reliability.

Impacts on consumer prices and domestic inflation

Tariffs don’t stop at the factory. When input prices rise, so do retail prices and delivery costs. Consumers pay more for electronics, food, clothing and home goods—sometimes with little explanation. In the UK, where inflation has already strained budgets, this added pressure worsens inequality and slows economic recovery for working families.

Some of the hardest-hit sectors rely on goods from tariff-affected countries with limited substitutions. Furniture, processed foods, and tech devices become more expensive or harder to find consistently. For households already managing higher energy costs and mortgage rates, these shifts in prices reduce purchasing power and limit choices, adding further stress to already tight financial margins.

Trade relations and diplomatic strain with the US

Despite their close ties, the UK and US have faced disputes over trade rules and access in recent years. Tariffs on steel, aluminium and whisky strained the relationship and slowed progress on a long-promised trade deal between the countries. Trust was shaken, and industries lost access to a vital export market without warning.

Negotiations remain fragile and subject to changes in US domestic politics and global economic sentiment. Political shifts in Washington make long-term agreements harder to reach and finalise, especially in strategic areas. The UK, now outside the EU, must navigate these talks alone—without the bloc’s influence. This creates uncertainty for British firms that depend on US markets or investment, limiting planning and long-term growth decisions.

Strategic trade diversification: rethinking global partnerships

To reduce exposure, the UK has been broadening its trade base across continents and sectors. Deals with Australia, New Zealand and members of the CPTPP open new routes for goods and investment. These agreements aim to spread risk and reduce the impact of volatility elsewhere, especially in traditionally US-dominated markets.

Diversification also brings opportunity for innovation and market agility. New markets mean new demand, often in fast-growing economies with rising middle classes. For the UK, this shift can strengthen its role as a flexible trading nation—less bound to any single partner and better equipped to respond to shocks, like tariff disputes or regional slowdowns, with greater autonomy.

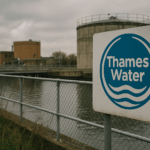

Domestic industry: building resilience from within

Beyond trade strategy, the UK is investing in local production to bolster internal capacity. Tariffs have exposed just how dependent some industries are on imported goods for critical functions and operations. By reshoring key sectors—like pharmaceuticals, energy and defence—the country aims to reduce that vulnerability and create new jobs that support long-term goals.

Incentives include tax breaks, research funding and support for innovation that accelerates independence. The goal is not just insulation from foreign policy swings, but long-term strength through investment. A self-reliant industrial base also gives the UK more leverage in future trade talks, helping it secure deals on its own terms and protect core sectors from sudden external shocks.