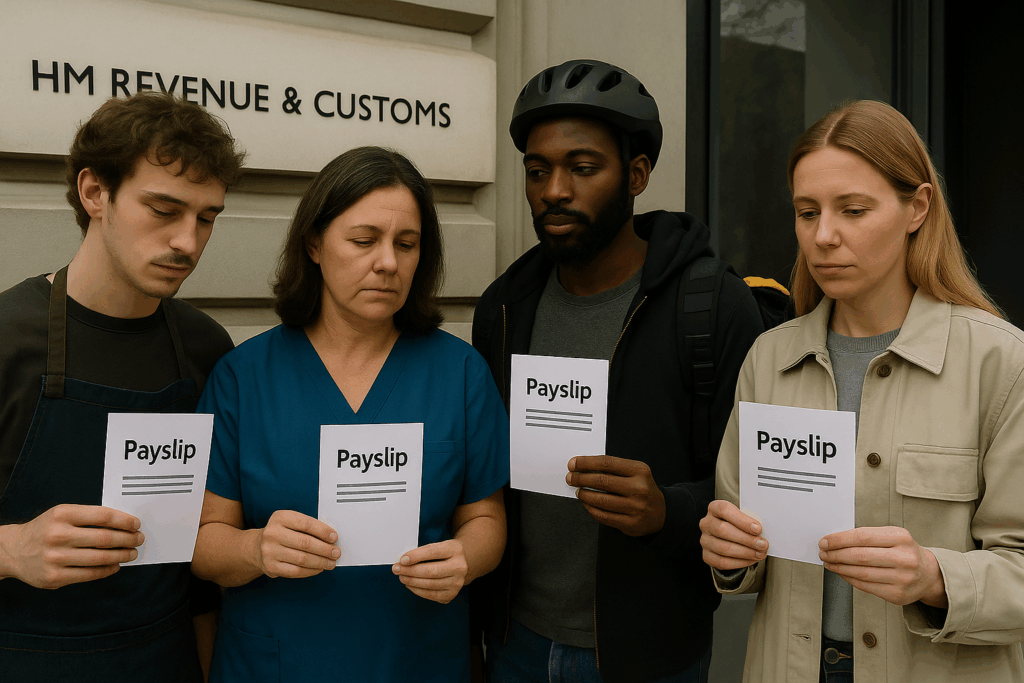

Every year, millions of workers across the UK contribute to the National Insurance (NI) system, a key pillar supporting the welfare state, funding everything from the NHS to state pensions. For most, NI is a silent deduction on their payslips—easy to overlook, yet crucial to sustaining the social safety net. But as economic conditions evolve and governments reevaluate taxation strategies, even small changes to NI rules can have wide-reaching effects. Recently, the government introduced adjustments to the income threshold for National Insurance exemptions, a move that promises to reshape the financial reality for a large segment of the working population.

While any update to tax policy is often cloaked in complex terminology and overshadowed by political spin, the shift in NI exemption limits deserves attention. Behind the bureaucratic jargon lies a policy shift with tangible implications: more take-home pay for some, uncertain outcomes for others, and a host of nuanced consequences that ripple across sectors and income brackets. This article takes a deep dive into the new changes, demystifies their purpose, and unpacks what they might mean for workers trying to stretch their income in a turbulent economic climate.

Understanding the adjustment: what’s changed?

The core of the recent change lies in the increase of the earnings threshold before National Insurance contributions are triggered. Previously, employees in the UK would begin paying NI once their income surpassed £12,570 annually. However, the threshold has now been raised to £13,000, aligning more closely with the personal income tax allowance. This shift is being framed as a “cost-of-living relief measure,” part of broader government efforts to provide financial breathing room for households facing inflationary pressures, rising energy costs, and an increasingly expensive post-pandemic landscape.

The government’s rationale is relatively straightforward: by increasing the exemption limit, workers get to keep a bit more of their earnings, which could cumulatively make a noticeable difference over time. For someone earning £13,000 or less annually, this means no longer paying Class 1 contributions—a relief that can feel substantial when every pound matters. Even those earning just above the new threshold will see a reduction in their total NI bill. This could amount to several hundred pounds in annual savings, depending on individual income levels and hours worked.

However, this move is not without its critics. Policy analysts point out that the largest proportional benefits will likely go to part-time workers or those in lower-paid roles, while middle-income earners may see relatively modest savings. Furthermore, there are concerns about how this reduction in contributions could impact long-term entitlements—especially for pensions—since lower contributions might translate to fewer qualifying years for full state pension access. While the Treasury assures that safeguards will be maintained to protect workers’ benefit eligibility, the details remain murky, leading to unease among those trying to plan for the future.

Winners and worriers: who gains, who hesitates?

For many low-wage earners, especially those juggling multiple part-time jobs or working in sectors like hospitality, caregiving, or retail, the raised NI threshold is a welcome change. It provides immediate relief without requiring any action—more money in your pocket simply because the rules have shifted. This could be especially meaningful for younger workers and single parents who often operate on tight monthly budgets. The increased exemption also complements other support schemes like Universal Credit, potentially reducing clawback effects and allowing people to retain a higher portion of their income.

Yet, not everyone is celebrating. For freelancers and self-employed individuals paying Class 2 and Class 4 contributions, the story is a bit more complex. Although adjustments to thresholds will ripple into these categories, the self-employed often operate under different sets of rules, with unpredictable income patterns that don’t always align neatly with standardized tax brackets. While some may benefit, others may find the net result negligible—or worse, confusing to navigate.

There’s also an institutional concern: the long-term sustainability of the National Insurance Fund. Reduced contributions on a national scale could translate into decreased resources available for public services, pensions, and social support. Economists caution that while short-term fiscal relief is politically attractive, it must be balanced against the potential weakening of foundational social programs. If the goal is to modernize how we fund welfare in a post-pandemic economy, broader reforms might be necessary beyond simply tweaking thresholds.

Implications for the broader economy

The ripple effects of the NI exemption changes extend well beyond individual pay packets. Employers may also experience subtle shifts in workforce dynamics. For instance, jobs that hover just above the exemption line might become more attractive to workers, increasing competition for certain roles while others—those just below the threshold—could see less enthusiasm from job seekers. This could drive slight distortions in hiring or scheduling decisions, particularly in industries with high staff turnover or hourly pay structures.

Moreover, the policy might contribute, albeit marginally, to increased consumer spending. When workers retain more of their income, they are more likely to spend it, thereby stimulating local economies. Retailers, service providers, and small businesses could see incremental boosts in revenue as a result of this increased disposable income. However, given the modest scale of the change—approximately £125 annually for some workers—the effect on macroeconomic indicators like GDP or inflation is expected to be minimal.

In the political arena, the government’s move could be seen as an attempt to regain public favor amidst broader economic dissatisfaction. After months of industrial action, inflation-fueled anxiety, and rising public debt, such policy tweaks offer a signal—however small—that fiscal relief is being prioritized. But political analysts warn that temporary relief measures may not be enough to sway public sentiment unless accompanied by a more comprehensive economic recovery strategy. Voters increasingly demand clarity, not just on what the government is doing, but why—and how it will impact their lives five, ten, or twenty years down the line.

Navigating change with awareness

In a time of economic instability and shifting policy landscapes, workers must remain informed and vigilant. While the new NI exemption limit presents a net-positive development for many, it is not a panacea. It offers short-term relief and signals an effort to ease financial strain, but it does little to address the structural challenges embedded within the UK’s social security and tax systems. From future pension qualifications to the sustainability of public services, the broader implications demand ongoing scrutiny.

For now, employees should take the time to understand how these changes affect their specific circumstances. Whether it’s revisiting paycheck deductions, recalculating self-employment contributions, or seeking advice on retirement planning, proactive financial literacy has never been more essential. In the end, this isn’t just about saving a few pounds each year—it’s about understanding how small fiscal policies shape the wider social contract we all participate in.